Collaborating

Objectives

- Explain what remote repositories are and why they are useful.

- Explain what happens when a remote repository is cloned.

- Explain what happens when changes are pushed to or pulled from a remote repository.

Version control really comes into its own when we begin to collaborate with other people. We already have most of the machinery we need to do this; the only thing missing is to copy changes from one repository to another.

Systems like Git allow us to move work between any two repositories. In practice, though, it’s easiest to use one copy as a central hub, and to keep it on the web rather than on someone’s laptop. Most programmers use hosting services like GitHub or BitBucket to hold those master copies; we’ll explore the pros and cons of this in the final section of this lesson.

Git is:

- distributed version control system (don’t worry about the details)

- designed to be fast and efficient

- Has an awesome logo octocat

- FREE

Git can set up a repository on your local computer - no connection to a big server or online is needed to make it work!

GitHub

GitHub is where code is collected online.

Show a project on GitHub (further justification for learning).

GitHub connects your local repositories to the online world and allows your project to get social

You can clone or fork other people’s repositories (more on that later).

Easily see changes that have been made (and when) and who made the changes

citable!

C.V./resume line!

github.com?

GitHub is a site where many people store their open (and closed) source code repositories. It provides tools for browsing, collaborating on and documenting code. Your home institution may have a repository hosting system of it’s own. To find out, ask your system administrator. GitHub, much like other forge hosting services (launchpad, bitbucket, googlecode, sourceforge etc.) provides :

- landing page support

- wiki support

- network graphs and time histories of commits

- code browser with syntax highlighting

- issue (ticket) tracking

- user downloads

- varying permissions for various groups of users

- commit triggered mailing lists

- other service hooks (twitter, etc.)

- even hosting simple websites (like my personal webpage)

Give a quick tour of GitHub

EXERCISE: Show everyone how to make a new account. If they have an account already, ask them to help their neighbors get started.

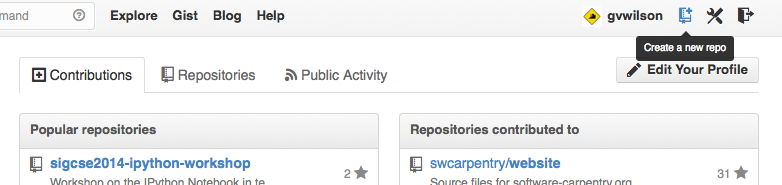

Let’s start by sharing the changes we’ve made to our current project with the world. Log in to GitHub, then click on the icon in the top right corner to create a new repository called planets:

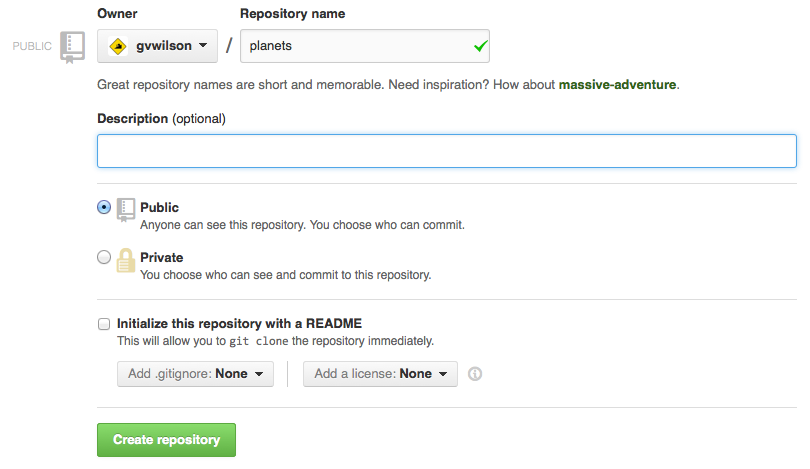

Name your repository “planets” and then click “Create Repository”:

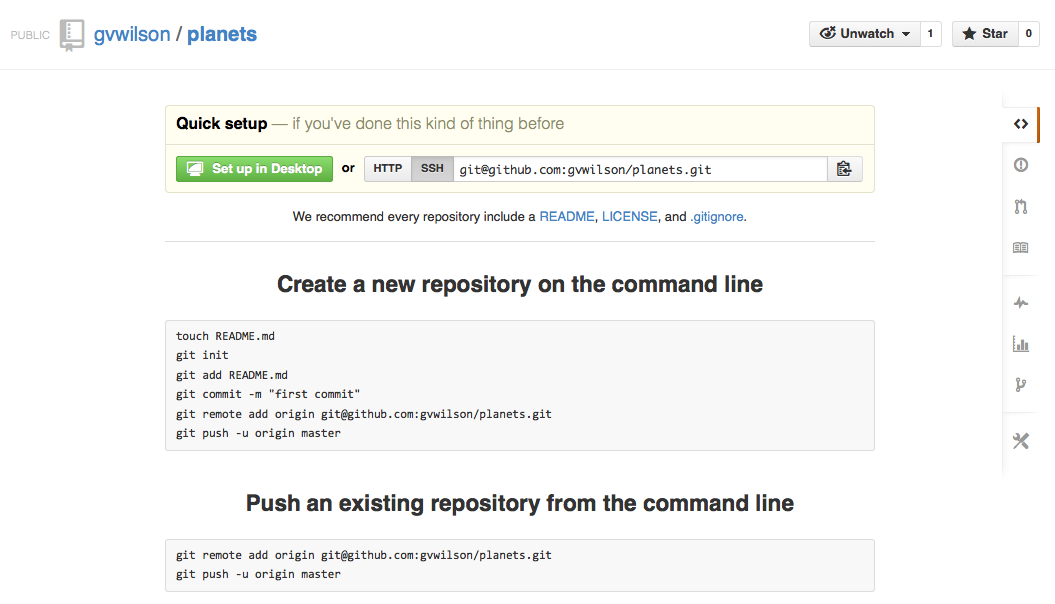

As soon as the repository is created, GitHub displays a page with a URL and some information on how to configure your local repository:

This effectively does the following on GitHub’s servers:

$ mkdir planets

$ cd planets

$ git initOur local repository still contains our earlier work on mars.txt, but the remote repository on GitHub doesn’t contain any files yet:

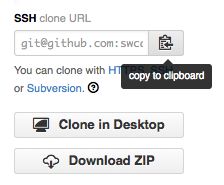

The next step is to connect the two repositories. We do this by making the GitHub repository a remote for the local repository. The home page of the repository on GitHub includes the string we need to identify it:

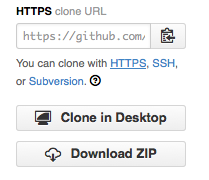

Click on the ‘HTTPS’ link to change the protocol from SSH to HTTPS.

HTTPS vs SSH

We use HTTPS here because it does not require additional configuration. After the workshop you may want to set up SSH access, which is a bit more secure, by following one of the great tutorials from GitHub, Atlassian/BitBucket and GitLab (this one has a screencast).

If want to know more about SSH we invite you to check our small lesson about it.

Copy that URL from the browser, go into the local planets repository, and run this command:

$ git remote add origin https://github.com/vlad/planets.gitMake sure to use the URL for your repository rather than Vlad’s: the only difference should be your username instead of vlad.

We can check that the command has worked by running git remote -v:

$ git remote -vorigin https://github.com/vlad/planets.git (push)

origin https://github.com/vlad/planets.git (fetch)The name origin is a local nickname for your remote repository: we could use something else if we wanted to, but origin is by far the most common choice.

Once the nickname origin is set up, this command will push the changes from our local repository to the repository on GitHub:

$ git push -u origin masterCounting objects: 9, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (6/6), done.

Writing objects: 100% (9/9), 821 bytes, done.

Total 9 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0)

To https://github.com/vlad/planets

* [new branch] master -> master

Branch master set up to track remote branch master from origin.The first time we push, we add the option -u or --set-upstream. This tells git that the master remote branch is our “main branch”, which will be useful later in comparing the status of local and remote repositories.

Show that the files now exist online

Proxy

If the network you are connected to uses a proxy there is an chance that your last command failed with “Could not resolve hostname” as the error message. To solve this issue you need to tell Git about the proxy:

$ git config --global http.proxy http://user:password@proxy.url $ git config --global https.proxy http://user:password@proxy.urlWhen you connect to another network that doesn’t use a proxy you will need to tell Git to disable the proxy using

$ git config --global --unset http.proxy $ git config --global --unset https.proxy

Password Managers

If your operating system has a password manager configured,

git pushwill try to use it when it needs your username and password. If you want to type your username and password at the terminal instead of using a password manager, type$ unset SSH_ASKPASSYou may want to add this command at the end of your

~/.bashrcto make it the default behavior.

Our local and remote repositories are now in this state:

The ‘-u’ Flag

You may see a

-uoption used withgit pushin some documentation. It is related to concepts we cover in our intermediate lesson, and can safely be ignored for now.

We can pull changes from the remote repository to the local one as well:

$ git pull origin masterFrom https://github.com/vlad/planets

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

Already up-to-date.Pulling has no effect in this case because the two repositories are already synchronized. If someone else had pushed some changes to the repository on GitHub, though, this command would download them to our local repository.

Add a README.md file on the browser. Demonstrate pulling changes back down to your machine Add NASA data to my local repository (http://www.nasa.gov/open/data.html). Push changes

For the next step, get into pairs. Pick one of your repositories on Github to use for collaboration.

Practicing by yourself

If you’re working through this lesson on your own, you can carry on by opening a second terminal window, and switching to another directory (e.g.

/tmp). This window will represent your partner, working on another computer. You won’t need to give anyone access on Github, because both ‘partners’ are you.

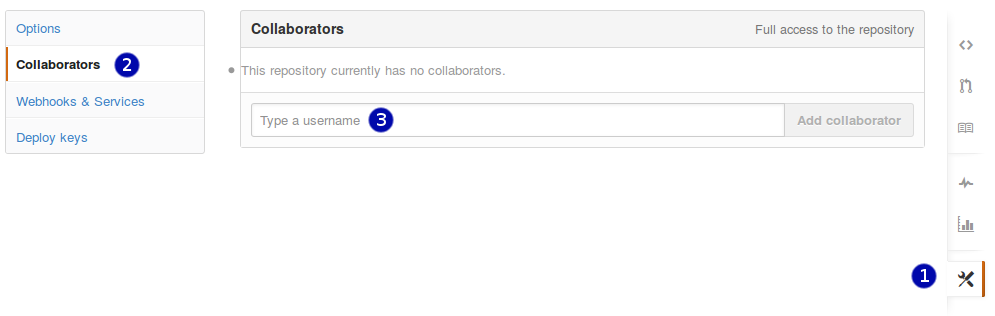

The partner whose repository is being used needs to give the other person access. On Github, click the settings button on the right, then select Collaborators, and enter your partner’s username.

Demonstrate how to add collaborators

The other partner should cd to another directory (so ls doesn’t show a planets folder), and then make a copy of this repository on your own computer:

$ git clone https://github.com/vlad/planets.gitReplace ‘vlad’ with your partner’s username (the one who owns the repository).

git clone creates a fresh local copy of a remote repository.

The new collaborator can now make a change in their copy of the repository:

$ cd planets

$ nano pluto.txt

$ cat pluto.txtIt is so a planet!$ git add pluto.txt

$ git commit -m "Some notes about Pluto" 1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 pluto.txtthen push the change to GitHub:

$ git push origin masterCounting objects: 4, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 306 bytes, done.

Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

To https://github.com/vlad/planets.git

9272da5..29aba7c master -> masterNote that we didn’t have to create a remote called origin: Git does this automatically, using that name, when we clone a repository. (This is why origin was a sensible choice earlier when we were setting up remotes by hand.)

We can now download changes into the original repository on our machine:

$ git pull origin masterremote: Counting objects: 4, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 0), reused 3 (delta 0)

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done.

From https://github.com/vlad/planets

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

Updating 9272da5..29aba7c

Fast-forward

pluto.txt | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 pluto.txtKey Points

- A local Git repository can be connected to one or more remote repositories.

- Use the HTTPS protocol to connect to remote repositories until you have learned how to set up SSH.

git pushcopies changes from a local repository to a remote repository.git pullcopies changes from a remote repository to a local repository.git clonecopies a remote repository to create a local repository with a remote calledoriginautomatically set up.

Challenge

Create a repository on GitHub, clone it, add a file, push those changes to GitHub, and then look at the timestamp of the change on GitHub. How does GitHub record times, and why?